Kunst und Protest im Japan der 60er Jahre

This is our dwelling, where we who are already dead live with those who are not yet dead. We are silent together and we talk to each other, listen to each other and to the silence. As in a Noh play there are encounters between the ghosts and the living, the undead, the demons, the lunatics, the outsiders, the saints. We do not come to rest, because we are preoccupied with so many unfinished stories. We sit here and wait for guests, as if in an eternal waiting room. In the meantime we are absorbed with ourselves and with what is commonly thought of as beauty. We have perfected death and declared it a question of aesthetics. We have forgotten the revolts, it seems to us. For a short time in Japan’s history the revolts had beauty, power and possibly even the potential for real change.

This is our dwelling, where we who are already dead live with those who are not yet dead. We are silent together and we talk to each other, listen to each other and to the silence. As in a Noh play there are encounters between the ghosts and the living, the undead, the demons, the lunatics, the outsiders, the saints. We do not come to rest, because we are preoccupied with so many unfinished stories. We sit here and wait for guests, as if in an eternal waiting room. In the meantime we are absorbed with ourselves and with what is commonly thought of as beauty. We have perfected death and declared it a question of aesthetics. We have forgotten the revolts, it seems to us. For a short time in Japan’s history the revolts had beauty, power and possibly even the potential for real change.

In January 1968 a dialogue appeared in the film magazine Eiga Geijutsu (Film Art) between Nagisa Oshima, the ultra-left film-maker, and Yukio Mishima, the conservative writer who maintained a private army and two years later would instigate coup and commit seppuku on its failure. They conducted a fervent and controversial debate on the connection between student protest and media reality. Politics and images – this is the heading under which the events of the 1960s in Japan (and worldwide) can be viewed.

What happened in the ten years between May 1960 (Ampo = Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America) and December 1970 (death of Yukio Mishima), the same year in which the first Asian Expo took place in Osaka – and do these two events have anything tod o with one another?

Upheaval and rebellion, the conquest of the streets, but also the struggle for the control of images. On the other side the tradition of aesthetics, beauty, refinement and the perfection of the imperfect. Centuries-old mastery, revered and admired in Japan and abroad.

The view of Japan is almost always formalistic, one that attempts to interpret the gesture, the sign, the code. The old and new Western aficionados and interpreters of Japan, Lafcadio Hearn, Roland Barthes, Claude Levi-Strauss, Donald Richie, Ruth Benedict, Alex Kerr, Florian Coulmas, Chris Marker, all succumbed, or still succumb, to the mystery of form and the fascinating form of mystery. The diffusely indistinct aesthetic enigma of the ‘other’ blurs the view of a reality that beyond its fetishisation from outside has more to offer than the idealisation of tradition.

Mishima, the nationalist aesthete and political revolutionary, and Oshima, the radical renewer of Japanese film. Between these two figures unfurls the panorama of a confrontation which played out in the 1960s. A politics of the body – a liberation of the body.

Omotenashi (= the Japanese concept of hospitality and customer service) takes the form of a simple experimental setup: the confrontation of highly aesthetic objects, craftwork and everyday objects both ancient and modern with vestiges of the political and artistic protest of the 1960s.

Very little is known in the West about what occurred in Japan during these years. And on a closer look it is all the more surprising that nothing seems to remain of it at all today. Europe had May ’68 in Paris, the United States had the protest against the Vietnam War. In Berlin the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot. But who knows of Michiko Kanba, the young woman who died on 15 June 1960 during the Ampo protests?

The writer Mishima once complained that the image of Japan (and its self-image) is too much informed by beauty and harmony. He would prefer to see more of the warrior than the art of flower arranging. The uprising, the revolts, of the 1960s appear to have been a short moment in which parts of Japanese society abandoned their internalised restraint, the socially expected patterns and norms, and aspired to change.

A fierce conflict broke out in the universities, and when farmers were to be dispossessed for the building of Narita Airport the protest broadened. Artists naturally also entered this field of political turmoil: dramatists like Terayama, film-makers like Oshima, Matsumoto, Teshigahara, musicians like Takemitsu, photographers like Moriyama, Araki, Hosoe. After only three issues Japan’s most famous photography magazine, Provoke, revolutionised the way in which such publications had to look. Images of street protest and the US military base on the island of Okinawa were juxtaposed with those celebrating a new and freer sexuality.

A young graphic designer called Yokoo Tadanori had the main role in a key film of the Japanese Nouvelle Vague, Oshima’s Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (1969), a film which put the era’s spirit of change under the magnifying glass. A thoroughly fragmented narration that uses a range of aesthetic and dramaturgical elements: street theatre, interviews with the actors, the alteration of colour and black and white, textual inserts, scenes of student unrest. An entirely unknown, handsome young man from the homosexual underground was cast in a film. Peter, who later worked with Kurosawa, turned Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses (Bara no soretsu, 1969) into a sensation. It is the story of Oedipus told with the means of the experimental film. Stanley Kubrick would find inspiration here for A Clockwork Orange.

The political protest died down; Japan’s rise to economic power attained a strong dynamic; the pressure to conform increased. Traces of the cultural upheaval have remained inscribed in the social fabric, but their original context is almost forgotten.

Omotenashi is an invitation to follow these traces. Much is only touched on; most of the images are simple photocopies and reproductions. Omotenashi is not an exhibition in the conventional sense. We simply open the doors to a space in which the trails left by some of those active during these years are visible and prompt the viewer to reflection and rereading.

7.1.2017

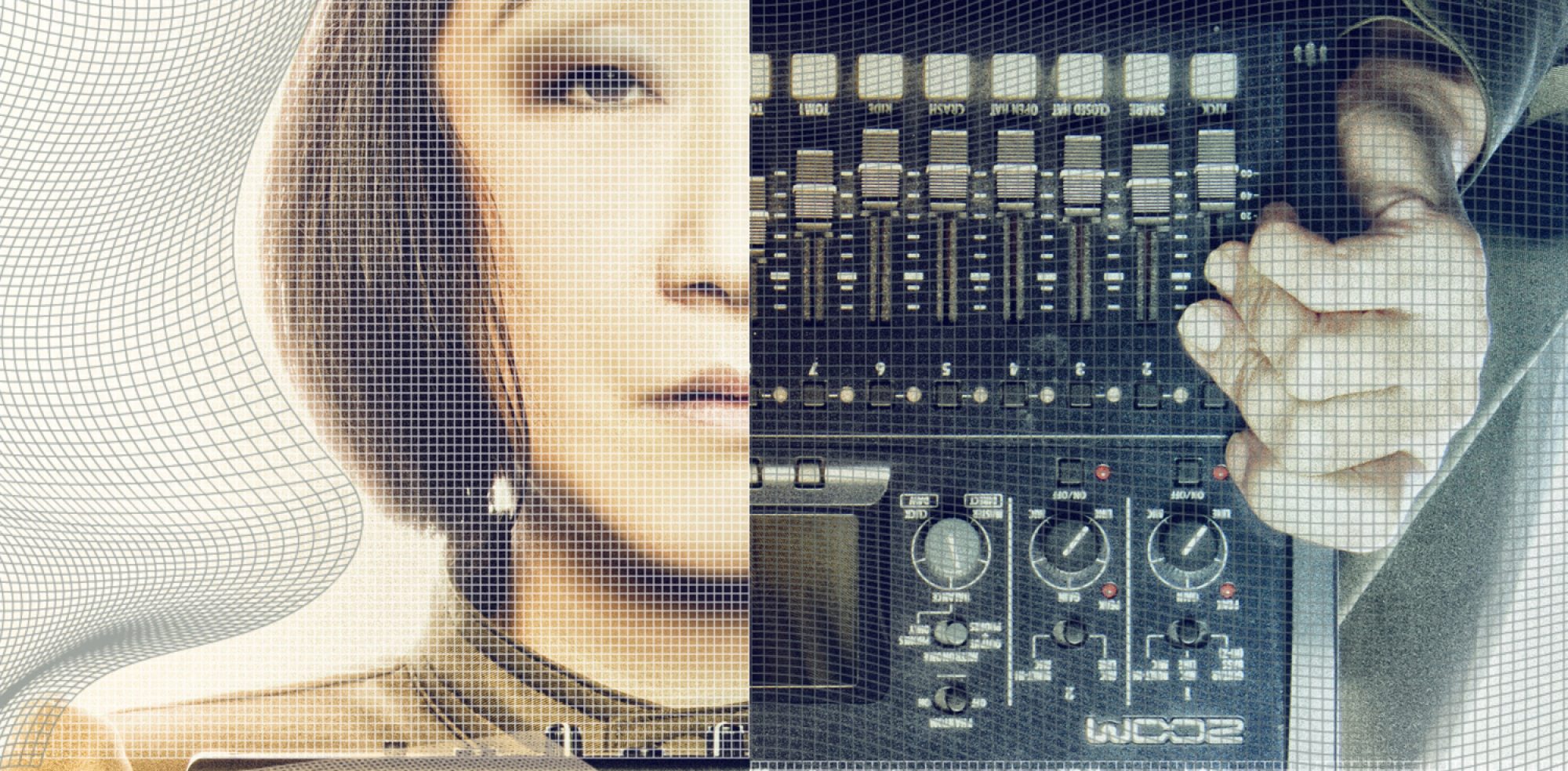

OMOTENASHI Live Event( German language):

Wir feiern das neue Jahr mit Lesung und Musik in der Ausstellung Omotenashi – Welcome to Ghosts + Guests

Kunst und Protest im Japan der 60er Jahre.

Manami N. präsentiert historische soundpieces und

SCHMALZ liest Texte von:

Mishima Yukio

Oshima Nagisa

Okamoto Taro u.a.

Einige der an diesem Abend präsentierten Texte werden zu diesem Anlaß erstmals auf deutsch vorgestellt.

07. Januar 2017 ab 19 Uhr

Im Rahmen der Ausstellung Omotenashi – Welcome to Ghosts + Guests.

kuratiert von Jan Philipp Frühsorge und Manami N.

in Kooperation mit Martin Mertens

Facebook Event seite:

https://www.facebook.com/events/386102595058134/